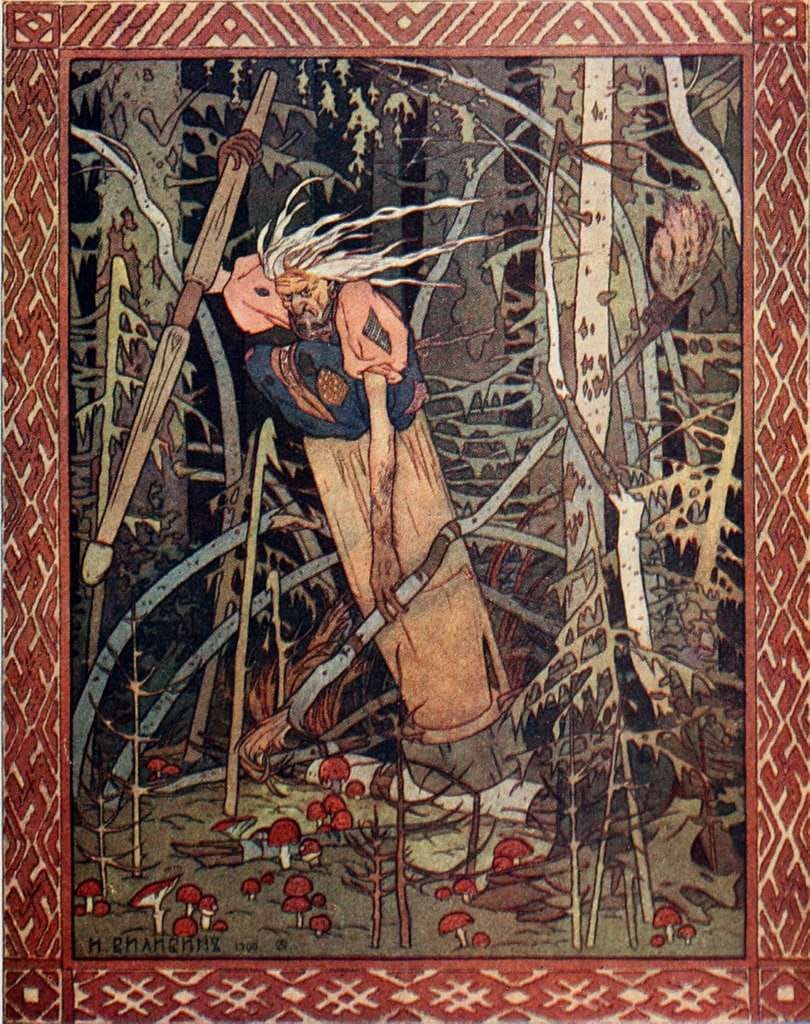

Note: Welcome to the first of my Slavic folktale retellings that rekindle the magic of the aging feminine from old stories. This project began in early 2023, when myth maker Angharad Wynne taught a group of women how to extract the bones from old folktales and reimagine them, layering in new perspectives, cultural elements, and more. I see these stories as channeled wisdom.

Rise Up, Red Fox features the Szeptucha, one of the most mysterious and sought after folk healers in Poland. Nearly every village in the eastern part of the country has one, but her powers and techniques reach far beyond the veil. Old ways, she will tell you, are not to be forgotten (or trifled with). I chose her because of the Szeptucha’s primordial connection to the earth and her lack of representation in classic Slavic folklore.

I even painted her as part of my year of being terrible at watercolour; A talisman, with the Slavic symbols for mother, strong family, and the goddess Mokosh embedded in the painting.

Finally, the story would have been spoken rather than written in medieval times. And, let’s face it, I am so down with imagining myself as a magical bard. So, I have recorded it. I hope you enjoy.

Many years ago . . .

the last girl child of Skowronów Wood had gone mute. All the rivers and trees, birds and even the wind went silent and cold the very moment her song died and no one knew how to change their fate. It seemed everyone had forgotten that the world required a certain kind of tending to.

Well, nearly everyone.

The angelic voices of the village’s girl children had once filled the forests. Each morning, they sang bright tunes of nature and the stars.

Since the obcych had come, the men had locked all the girls inside their homes. Protection, fathers said, from the strangers. But, shuddered away, one-by-one, the girls had grown mute, wan, empty. Ona was the last, a lone voice, until now.

“Hurry.” Marja rushed toward the small, A-frame cottage at the very edge of the wood. She clung to the memory of Ona dancing barefoot by the creek, her face bright with carefree laughter. It fuelled her frantic steps as her husband Piotr trudged behind in the frozen mist. “The old woman is the only way.”

The Szeptucha—Whisper—that’s what they called her, when they dared speak it. No one knew her true name. Not even the breeze dared to wander amongst the hellebore and the skunk cabbage to find her. Stories spoke of claws and teeth that shredded the bones of anyone who dared cross the forest. Taking the child to the Szeptucha assured them she’d be cured, everyone knew. But, Ona would not return the same, if any of them survived at all. Needless to say, the pale silence of their daughter deafened Marja and Piotr to the hag’s price.

As silent as his daughter, Piotr held the child tight to his chest. Marja banged on the Szeptucha’s door, heart racing. The old hag lumbered out. The porch creaked and swayed. A massive pelt writhed down her back. Thick red fur sprouted from beneath her coat. She waved them inside. Piotr laid the lifeless girl on the low, soft bed near the warm fire and took Marja’s hand. They trembled together, coaxing one another to breathe.

The Szeptucha placed her ear to the girl’s chest. A rasp. A rattle. These, the parents already knew, were not the sounds of a mere sniffle or a child who caught a chill. No herbs or broths would cure it.

“She requires a fox,” the old woman confirmed. “This is sickness all the way through.”

Piotr released Marja’s hand and reached for a bow and quiver by the door.

“No!” the hag boomed. “The old way.”

And, so . . .

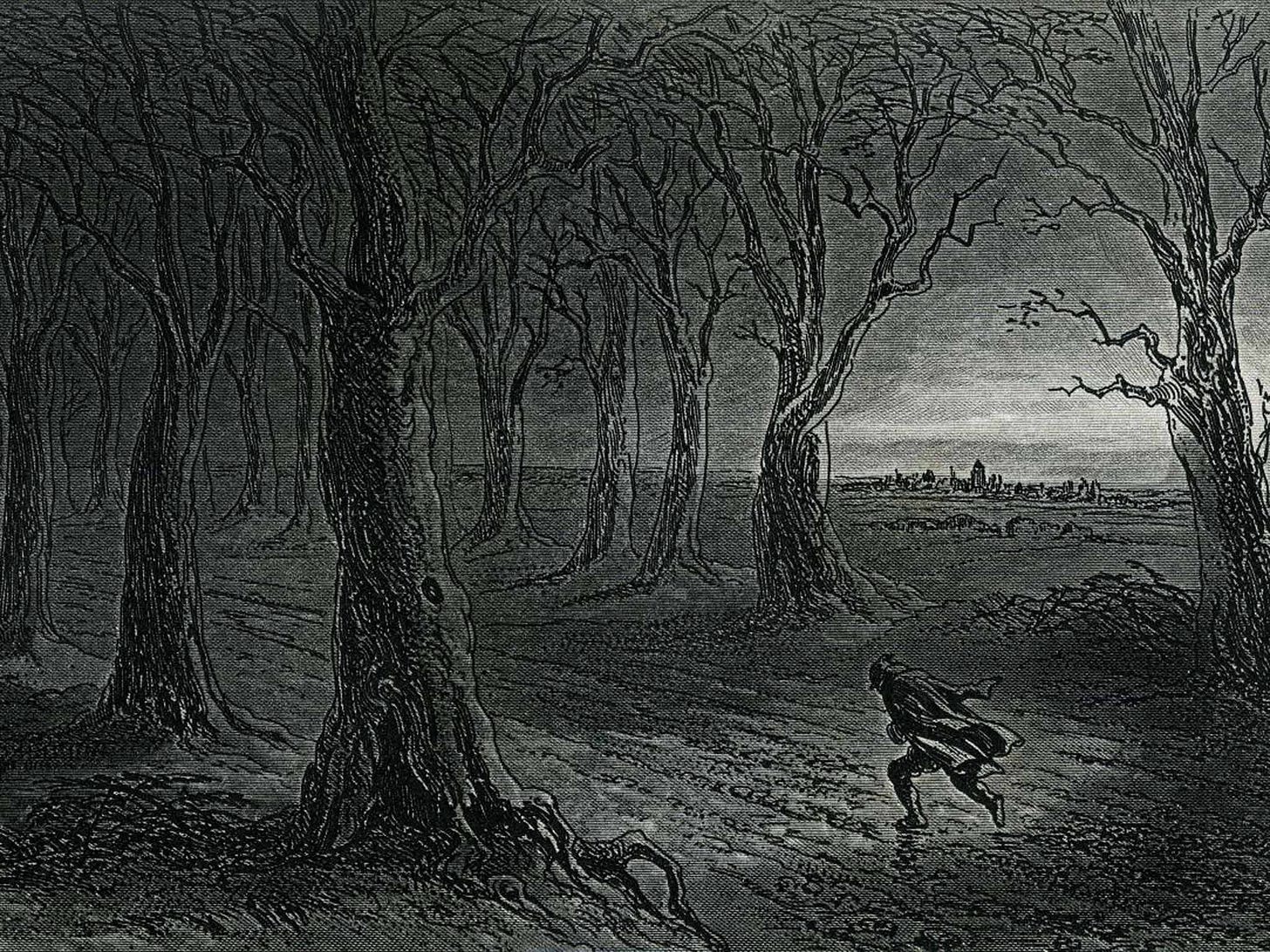

Piotr raced down the stone path and into the wood with nothing more than his senses for the hunt.

Marja wept as she gently brushed Ona's dull hair. She remembered how it once glowed a vibrant red when they braided wildflowers into it.

“How many?” the Szeptucha interrupted. She settled into a rocker beside Marja and pulled her babushka up over her head.

“What?”

“How many girls are gone?”

“All of them. We tried to protect them, but . . .”

The Szeptucha gazed at Marja with familiar yellow-green eyes. “And, your hair? Your song? I suppose they were protecting you too?”

“Old women don’t sing.” Marja pulled her own babushka tight around her head as the wind howled outside. “Please, just save the child.”

“Too old to sing? Are you too old to breathe?” The hag replaced Marja’s headscarf with a fox fur. Marja’s senses jolted to life for the first time since she was a young bride. She remembered the old songs and a hum churned in her belly.

With that, the Szeptucha flung open the door.

The bitterness of the wind turned her skin a frosty white. She breathed out in little more than a whisper, saying, “Powstań, rudy lisie. Rise up, red fox.”

In the forest, Piotr fought back his rage. Marja had refused to keep the girl out of the woods. He finally had to lock Ona in her room a week earlier, close and safe from the creep of the obcych. Yet, even with such precautions, their daughter laid near death. His chest grew tight. How had he let this happen? Now, the hag sent him after nothing but a foolish fox.

Suddenly, his ears caught the wind, “Powstań, rudy lisie.”

It rushed through him, and the trees, and shook the ground. Then, out from his own lips, it spoke again, “Rise up, red fox.”

The work of such magic startled him. Piotr had forgotten the old ways of those like the Szeptucha, but he recalled the old hunt. He hunted like his father had taught him. Ears perked. Nose tuned to any changes, any hint at all. When the fox sung, he would snap his hand around the neck of the beast and kill it. Anything for his girl.

The Szeptucha flooded him with his own memories. Of his sisters running through the forest. The glimpses of red tails darting down the paths. Marja’s orange-red hair, wild and spirited, that made him fall in love and take her as his bride. Ona’s songs. The fiery aliveness of all of the children in the realm of the red fox. The fierce hymns of girl and beast filled him with joy.

How he never wanted it to change, to bottle those precious moments.

Then, the aching quiet after the obcych came. How the songs went silent one-by-one. Ona had fought it. But, she too succumbed. Just kill it, he told himself.

A skitter rattled Piotr from his trance.

Tiny footprints appeared in the snow.

And, then, the crunch.

He stalked the creature like master against beast. He waited for the fox song so he could break its neck.

Yet, something was off.

He caught a glimpse of a pair of ears. Dull. Limp.

The tracks. Light. Weak. Signs of stool. Loose. Bloody.

His mind flashed to Ona. She, too. So light. So weak. His daughter’s face seemed to appear in the rocks and bark of the trees. Then, in the very eyes of the beast.

“Sing, girl. Sing,” he begged.

The fox shot up and attempted to make for a nearby snag. The hunter charged, ready to push himself to the limit to save his daughter. Within ten steps, Piotr caught up with his prey. He snatched the fox by the neck. Its eyes bulged. Piotr stiffened his grip.

“Sing!” he shouted.

Its jaws opened wide. A wailing like no other rose up. And, then, the fox went limp in his grasp. It slipped into the notch of Piotr’s arm, fallow and nearly weightless.

There was no song, he realized. The fox cried for death.

“Piotr!” he heard his wife calling. “Hurry!”

He tried once more to break the neck of the fox, but his heart had already shattered. Piotr tucked the fading creature in his coat and raced back through the forest.

At the hut, . . .

he found Ona choking and gasping for breath, that same fallowness in her form. The Szeptucha laid the fox beside Ona, both frail and colourless. The girl stiffened at the sight of it and began to weep.

“Get it away from her!” Piotr charged the bed.

But, his wife bared her teeth and stepped between him and Ona. Piotr sputtered and stared at Marja. She had grown larger, stronger, more intense. Never had her skin been so ruddy, her eyes so bright, even as a young wife. Had the Szeptucha changed her too? “What have you done to them?”

“Nothing that wasn’t necessary.” The hag brushed him off.

“You better be right, old witch, or I will have my turn with you,” Piotr threatened.

The Szeptucha ignored him and slid her crackled, enormous hands beneath the fox. Marja took Ona in her arms. In the night, a low hum rose up.

The hag's cure seemed a desecration. Yet, Ona's fading form was too dire to ignore. He had dismissed the old ways as folly, but now he needed them more than ever. If this was what it took to revive his daughter's spirit, he would have to yield.

A song began to weave a line.

A bright red string.

Then, another. And, another.

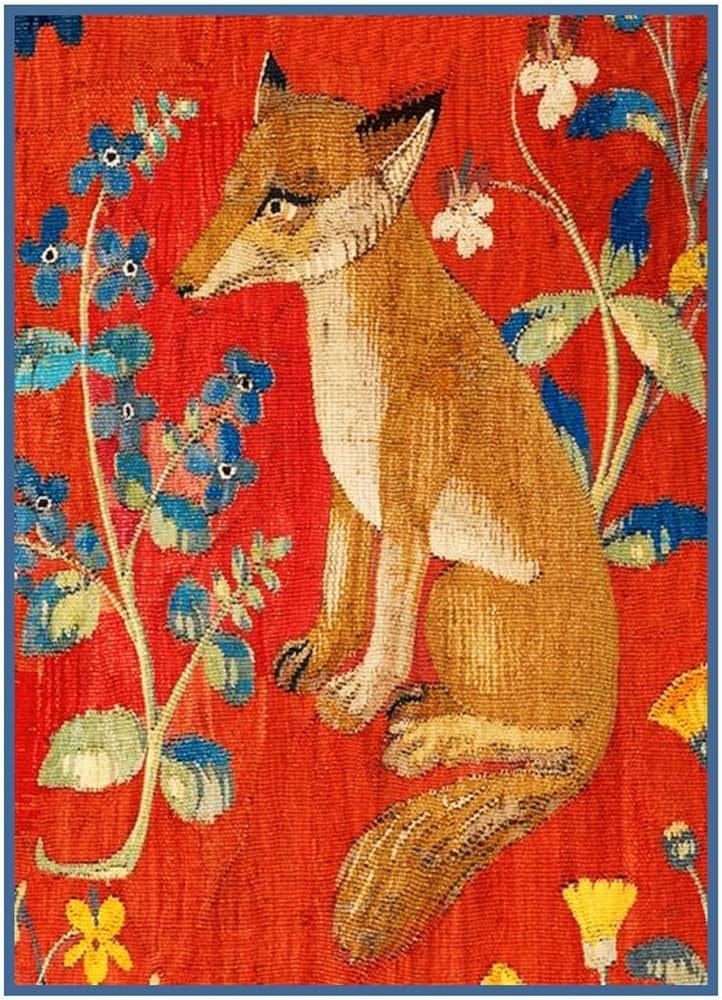

The push and pull of smoke and air wove a web of red cloth. It cocooned the child and the fox. The Szeptucha laid the entwined pair on the bed. A conjoined mass of crimson vines and tufts of fur woven like a tapestry. The child gasped. The fox jerked.

Piotr stalled in the doorway. His eyes bulged at the sight. His daughter lay wrapped in red tendrils, the fox's dim form merged with her waning body. He blinked hard, praying the nightmare vision would vanish. That his precious girl would be tucked safe in bed. Yet, the image remained.

A guttural cry escaped Piotr’s lips. His fists clenched, jaw locked, as shock boiled into blistering horror. How dare they tether his Ona to this wretched creature. She was too pure, too good. He lurched toward them, intent on tearing them apart.

“You are killing them!” he roared.

Marja once again planted herself firmly between him and the pair on the bed. Her eyes blazed with a ferocity that terrified Piotr.

“Let the hag work!” Marja stood sentinel, all her focus channeled into the tiny rise and fall of Ona's chest.

His wife’s demand stifled Piotr’s fury. The hag's cure seemed a desecration. Yet, Ona's fading form was too dire to ignore. He had dismissed the old ways as folly, but now he needed them more than ever. If this was what it took to revive his daughter's spirit, he would have to yield.

The Szeptucha flung her hands at him. “Go. You have done your part. Rest.”

Piotr collapsed . . .

on the rumpled reed mat in the loft. The day’s turmoil churned in his mind. Despair crept at the edges like a coming frost. He should have protected Ona, kept her closer. Piotr pressed his fists against his eyes and tried to stem useless tears.

There was still a chance. He reassured himself, grasped for hope. For Ona's life, he would relinquish any pride. His little girl, his own song. Finally, Piotr surrendered to sleep.

A noise woke him with a start just after dawn. Piotr bolted downstairs to find Marja and Ona in the front doorway. The red tail of a fox dashed down the stone path. Then, another. And, another.

“The girls!” Piotr cried out as he spotted the faces of children from the village, wild and alive, teeth bared, mouths wide. He stood transfixed as melodic voices drifted from the woods. At first as delicate as a whisper. Then, a symphony.

He watched them, flashes of color amongst the trees—crimson, emerald, sapphire. The village girls stepped from the dappled shadows into dawn's rosy glow. Their skin and hair glimmered auburn in the soft light. They moved with the quick, shivering sprint of the fox, bare feet soundless on the thawing forest floor.

In the doorway, Marja turned toward her husband. Her yellow-green eyes blazed, pelt become skin, mouth wide, teeth sharp. With hair as red as a fox tail, Ona waited for the children and the Szeptucha, then turned to her father in the morning mist.

Suddenly, fox song rang out on all of their lips.

“Powstań, rudy lisie. Rise up, red fox.”

They returned to the village, fox tails and all. The villagers called upon the tents of the obcych with offerings of bread and salt. The men unlocked their doors. The women pulled their old skins from their trunks. And, alongside the girl children of Skowronów Wood, Ona sung the song of the red fox as the Szeptucha danced wildly amongst the hellebore and skunk cabbage.