Author’s Note: Welcome to the second of my Slavic folktale retellings that rekindle the magic of the aging feminine from old stories. This project began in early 2023, when myth maker Angharad Wynne taught a group of women how to extract the bones from old folktales and reimagine them, layering in new perspectives, cultural elements, and more. I see these stories as channeled wisdom.

The Bones of the Beregini features the Bereginya, a spirit who created all, protector of the family and women in Poland. They are thought to be the predecessors to the Rusałka, water sprites now much maligned as dark, malicious creatures. It turns out that nefarious reputation depends on who is telling the story.

Enjoy.

The riverbanks are no place for men . . .

Some will tell you they are haunted by broken women. Daemonic sprites that linger at the edges, luring husbands and soldiers. Haunting beasts with hair like the bleeding roots of trees. They howl in the night, poised to devour your very soul down to the bones. Every word of it is true, with the omission of one crucial detail that begins with this very stara baśń—an old tale from a forgotten time.

So, let us begin.

Agneszka arrived in the cool waters of the River Łyna under the moon of the burning fires.

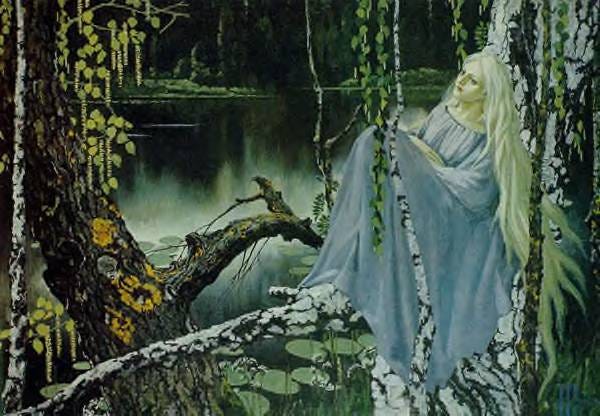

The old Beregini, as the sovereign ones were called, bestowed upon her a single duty—to watch over the mighty void between the worlds at the river’s source. And, so she lived for many years at the headlands, a solitary guardian at the water’s edge, with one foot in this world and one foot in the world of dreams.

Day after day, year after year, Agneszka dutifully served. For the men and boys, she kept their fishing nets full. For the women, she lit the way to the very edge of the veil where they danced and laid offerings for the sovereigns. And, it was beautiful.

But, in her fiftieth year, something changed . . .

The women abandoned their offerings. A blight turned the once-fragrant ferns a sickly black. The waters of the Łyna shrank until Agneszka was forced to retreat beyond the veil. She fell into despair, fearing the connection between the worlds was lost.

Stricken with sadness, she had not truly noticed Arek until his fourth or fifth visit. It started with little more than a murmur of a blessing over pears from his sack. But, he—like the women who used to come—could draw himself right up to the edge of the veil. He would reach out, as if he knew Agneszka stood just feet in front of him, and retreat when his hands met nothing but air. Then, like a little boy, he would sit on the edge of the river and begin to chant and pray to the bear and the stag, the twisted roots of the birch and what remained along the riverbed.

It was the way he spoke to the wind that drew Agneszka in. She had never heard a grown man weave words in such ways. Most spent their time with matters of the kingdom. One who sought matters of the soul brought her a new hope. Each day, he offered fox bones or a rabbit skull; loganberries plucked from trees; a basket woven from the bark of the birches. Then, he spoke a prayer to the river and set it free along the easy waters.

“Save us, Bereginya,” he called out. “Save us from ourselves.”

And, with that, the veil began to re-emerge . . .

Every day, he came to pray to the bear and stag, to speak to the wind, and by the next moon of the burning fires, Agneszka could plant a firm foot in both worlds once again.

Soon after, however, Arek’s eyes grew dim. His voice grew scratchy. Others had come like this, a stutter in their chests, a faintness in their heartbeat. Agneszka knew its name—the devil’s breath.

She cherished him with all her heart. So, she passed through the veil and stood before him with a cup. “Drink. Be clear.”

And, he was.

The next day, she waited for him. But, this time, Arek did not come alone. His breath heaved and he carried something—no, someone—in his arms. The handsome young man’s face had grown even paler than before.

Arek rushed to the river’s edge and pleaded, “Save my brother like you saved me, please.”

Agneszka could not bear his sadness. So, she became the wind, and crept up under the white silks that covered Arek’s arms. Grey-skinned and a bitter cold in his sweat, the child took in little more than sips of air. Deep into the night, she held the child afloat in the water between the worlds.

And, he was healed.

The next night, Arek bounded through the forest toward the river. He held a woman in his arms. Skin, translucent. Breath, long silenced.

“Save her as you saved me,” Arek begged. “Please, save my Róża.”

A woman, Agneszka thought. How long had it been since she had seen a woman on these banks? To revive her could bring the other women back as well. But, she knew that it would take more than the headwaters to save this dying flower. It required the rozpleciny—the unbraiding.

“There is something,” she told him. “But, it requires your heart and comes at a price.”

“Whatever is needed,” Arek said. “I submit to your will.”

And, so, Agneszka lifted the veil and cried out to the Beregini.

The waters of the dreamland rose up in a fury and flooded the river channel. With the young woman still in his arms, Arek waded into the fierce waters. Agneszka snaked out and around his feet to hold them in place on the slick rocks of the rapids. Arek’s knees buckled. The water thrashed. He stiffened and shook as the waters began to devour the woman in his arms, rattling the skin from her very bones. Arek persevered. Bloodied, yet serene. Gasping, but clear-eyed. Agneszka admired his courage and willingness to submit to this unplaiting of the body. The water stripped Arek and his love back, piece by piece, until he collapsed into the waves.

Agneszka swept him up just as his head dipped below the surface. She wrapped him in mats created from her hair. The very roots gently warmed and nourished Arek until he regained his senses.

Meanwhile, the old Beregini rose from the water, taking the bones of the young woman back beyond the veil. Their song filled the woods and the river stilled as the fire of day turned to the glimmer of night.

As the moon reached its peak in the sky, Róża emerged from the thick fog that had settled over the headlands. Arek laid there in disbelief, staring into the eyes of his love, as Agneszka spoke of the covenant which bonded the two worlds.

“All will be returned to you,” she said, placing only two conditions upon him. “Each week, on Saturday, you must grant Róża complete solitude. And, no daughter of hers will be raised in the faith of men. “

Arek praised the bear and the stag for such a blessing and sealed the vow.

As Agneszka hoped, Róża and Arek mended the old rifts.

The women returned to the river banks, the men to their nets. They worked the land back to health. The Beregini blessed their crops, and graced their people with the healing of the great weavers of the headlands. Agneszka brought hope to them all, a kingship to Arek, and Róża birthed his children.

“Two sons and now my beautiful Ona to extend the holy line, forged in the mists of the Beregini on the River Łyna!” Arek declared at his daughter’s presentation day.

All that while, he loved Róża without question. Each day, the two made the pilgrimage to the river with the bones of fish and skulls of rabbits to honor Agneszka and the old ones.

On a hill above, they buried the dead, so that they might move easily between the worlds. Each Saturday, Róża and the children returned to the headlands on the moon of the burning fires to renew her bond with her people. Each Sunday, Arek granted his raven-haired wife and violet-eyed Ona leave from Mass before the host was raised. They loved and the kingdom flourished

Others, however, were not so faithful.

The bounty of the Beregini had returned villagers to the countryside. There, they learned from the old ones and grew strong. They stoked burning fires of their own. But, lords and kings require dutiful and obedient armies.

“Fool,” the Generals mocked Arek. “Your witch queen has glamoured you.”

So, the king forbid Róża from taking the children to the burning fires more than once a moon cycle and the crops began to falter.

“She’s a demon,” the priests shouted.

“Not my Róża. Never,” Arek spoke, always defending her. But, he grew suspicious. So, the King forbid his wife and Ona from leaving the Mass before the host was raised. Within a month, marauders from the north invaded, ravaging the countryside.

Arek’s rage consumed him.

So, he crept into the forest at the height of the moon of the burning fires. There, he found the women of his kingdom. A thousand women, all dressed in white, but not entirely human. Those in the river, which ran deep and dreamy, slow in its manner, writhed and spun until their feet—no fins—peeked out from the water. Their legs had vanished. Even those of his beloved daughter.

On the banks, the villagers who had returned to the way of the Beregini ate heartily and hummed low hymns in the night. There, his sons served, delivering food and listening to the stories that the oldest, scaliest Beregini—with their fins for feet—told in the darkness.

Not a stone’s throw away, men starved and crops shrivelled, just as they had before Agneszka had taken him and Róża into the waters of the Łyna. Invaders set siege to the very castle where Róża gave birth to his sons. Agneszka had glamoured him, just as his generals said, and now he would lose his wife and family too. For a moment, Arek set his mind to fight.

Yet, the sight of Agneszka, who had saved him and Róża so long ago, drew him in. The more he watched, the more he longed to be at the side of his wife and children, stroking the root hair of the old weavers, devoured by their songs and stories. And, he remembered his own stories that pulled him to the river—that led him to Agneszka.

He caught her eye, and stood to greet her in the forest.

Instead of the greetings of an old friend, Agneszka’s eyes flashed with fury.

“You swore on the bear and stag!” she roared. “Now, look what your fear and pride brought with you.”

As Arek turned to see what had driven her to such rage, a horror set in. Behind him stood an army.

Such a force amassed could have levelled kingdoms. But, no man had ever tested his might against a force such as the Beregini. For their weapons were not blades and hammers. The old ones, aligned against anyone, could level entire worlds.

And, so they did.

Agneszka released a deafening shriek. The Beregini joined, one-by-one. Their piercing cries rattled the very skin from the bones of every soldier, the bones of every child, of every villager. The river tore up the path along its route, wild and impassable, an utter torrent over which no bridge could be built or heavy horse navigate.

Then, other than the rush of the water, the forest fell into utter silence.

The Beregini and all who stood against them simply vanished. Nothing more. No sons as heirs. No castles or lands. Nothing remained but the rage of the river and bones.

And, there it is, that one crucial detail left out of our tale.

The one of how men embellish stories to release themselves from the curse they laid. Tales of a water witch who murdered children because she could not curry the favor of a king. Tales of a terror that haunts the headlands. The howls. The horror. How fish-tailed furies lure men to their ends, chew them down to the bones.

That’s how the Beregini died and the Rusałka were born. So that men could soothe themselves in the belief that the insanity of wild women unleashed its frenzy at the edge of the veil. Let them believe it. Let them tell you the river is no place for any man at all.

A frenzy, indeed.

But, Agneszka will call and you will find yourself standing on the banks of the River Łyna. Do not ignore it, but do not expect to return the same. The ancient ones with hair like roots and blood will lure you right down to the water and pull you through the veil without mercy. Not to toss you in and leave you for dead, but to rattle the very skin from your bones so that you may pass between the worlds and learn of all that was lost.